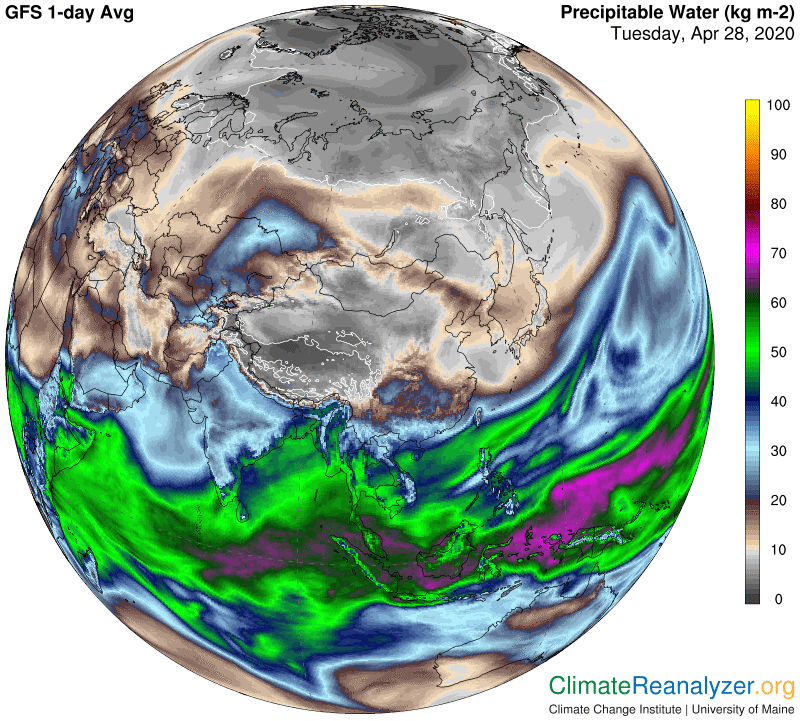

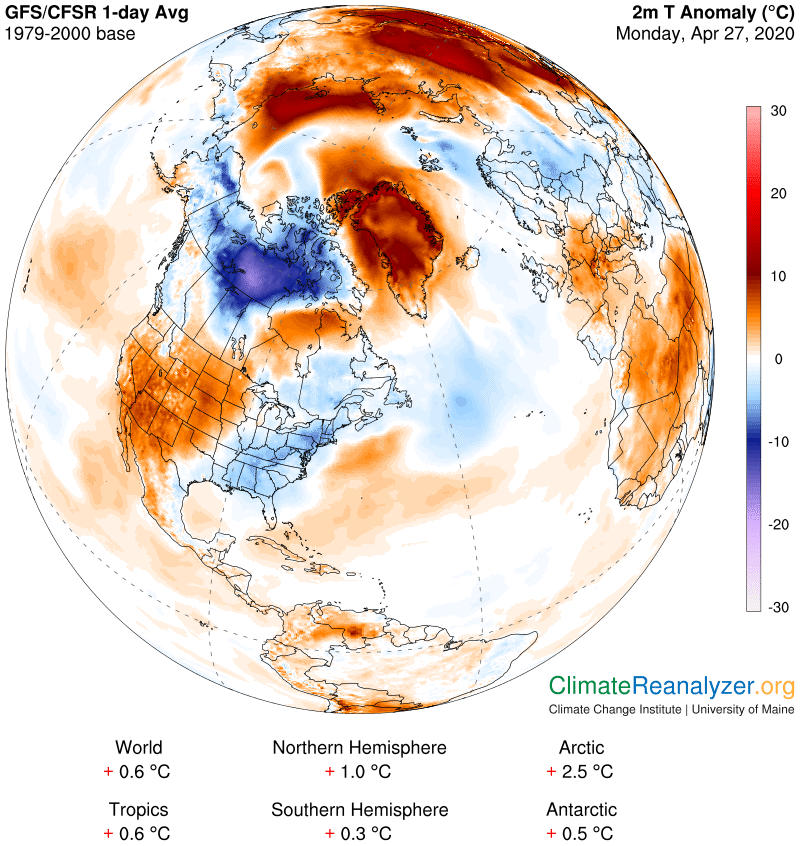

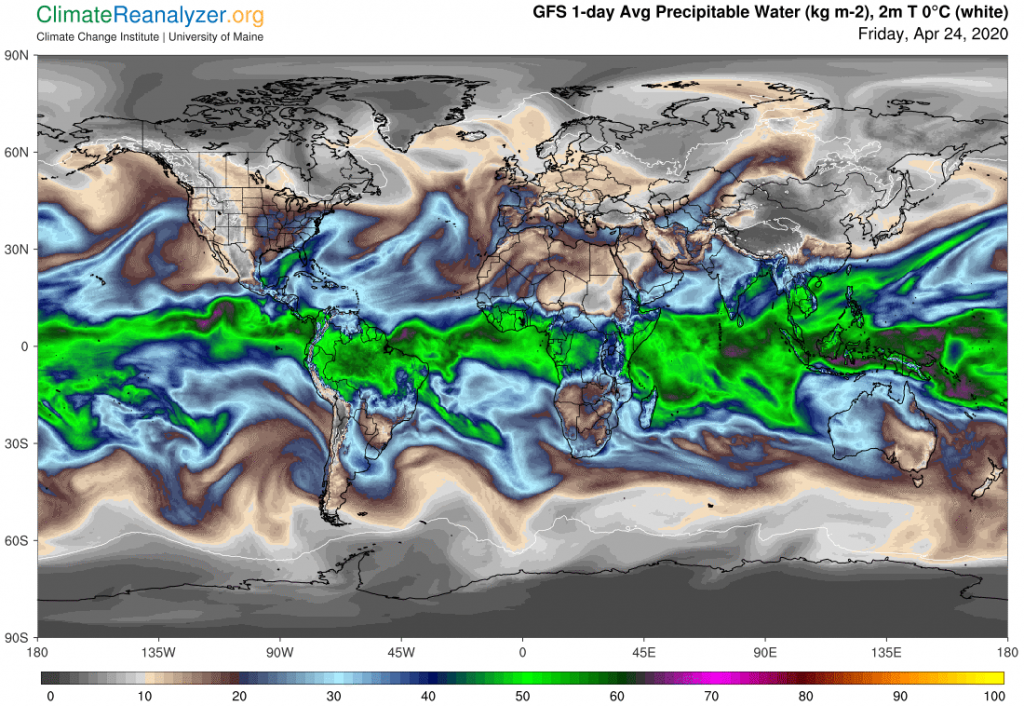

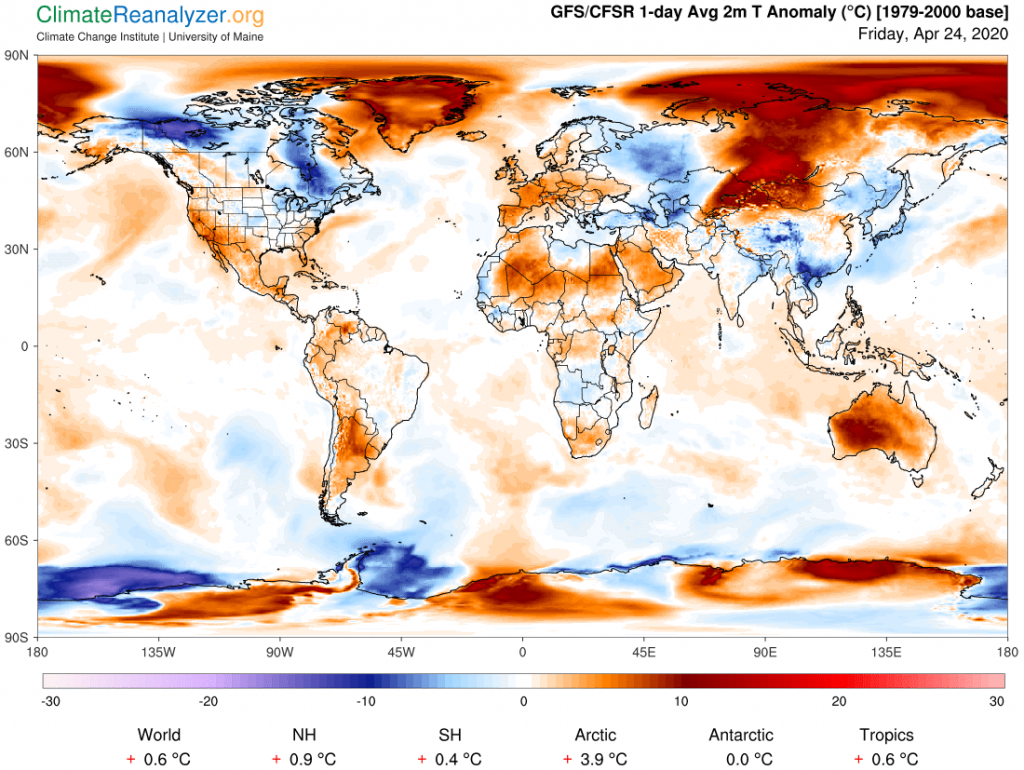

The theory I have been talking about developed after I became curious to know the reasons for the large regional temperature anomalies that show up every day on the Weather Maps, and why their sizes, shapes and locations keep changing all the time, in so many different ways. What I found was that every one of these things could be explained in a satisfactory way through studies involving those spiky-looking streaming pulses of large amounts of precipitable water (PWAT) that show up in a prominent way on the dedicated PWAT map. In order to get the full story about how and why the pulses have originated, the journeys they make, how the stream beds change along the way, their final stages and so on, these could only be be deduced after putting together information found on still more maps, as explained in a number of previous letters.

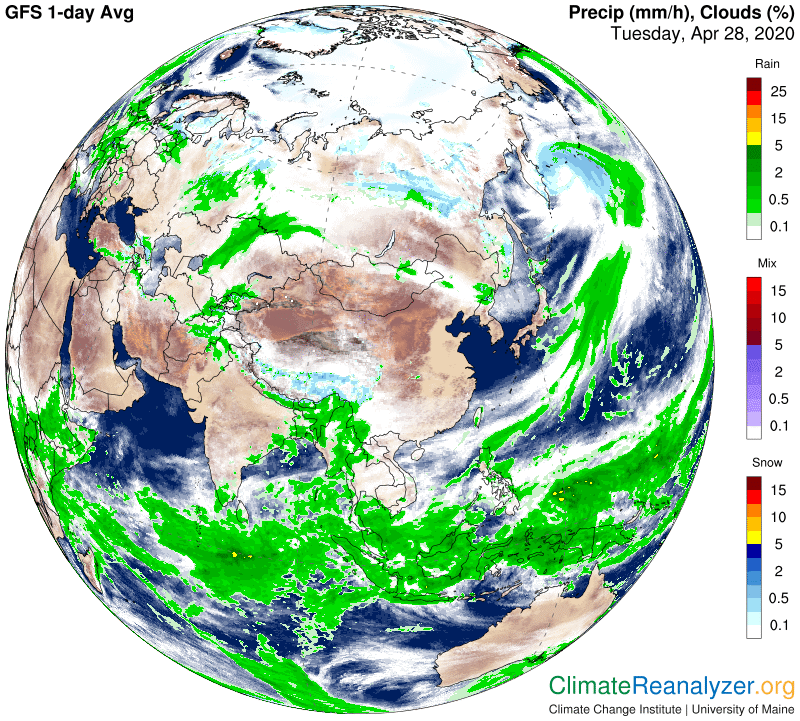

Now something different, but related, has come to mind. All during this study process I have noticed that the high-flying PWAT streams have been intermittently producing clouds and releasing precipitation, mostly in the form of rain, therefore lightening up their load, as they made their circuitous outbound journeys. The albedo cooling effect of the clouds had to be taken into account as a warming reduction. Other than these things I have not paid much attention to this apparent sideshow. It turns out, naturally enough, that all these precipitation events are precisely the same ones that meteorologists are looking at and find intensely interesting for reasons of their own. They are delivered by exactly the same streams that deliver the greenhouse warming energy I have been so focused upon. All of us can thereby be led to appreciation of the fact that these streams are producing two of the most important factors in the makeup of every climate zone on Earth’ They do so by applying several different properties of the same molecular material, water, in two completely different ways. Nature certainly has an efficient way of doing things, and it all makes sense.

Anyway, meteorologists must also wonder about the circumstances surrounding the origins of these streams, but I am not sure about what all they know and can share. The ideas I have come up with thus may or may not be useful to them. As expressed in several recent letters, I have picked out certain types of locations that seem to best qualify based on their meeting two specific requirements. One was the presence of a good-sized body of seawater having a surface temperature of not less than 25C. This temperature would provide enough energy to propel updrafts of winds carrying newly born vapors all the way up to a level where jetstream winds live and do their business. Temperatures under 25C would not be quite adequate for that purpose while those above would be fine, and would probably also be responsible for higher evaporation rates that would add more vapor to the load going up.

Second, these updrafts, in order to reach their proper altitude of destiny, would need an unobstructed pathway. A clear sky should best perform this task while those heavily clouded might normally fail. Partly clear or lightly clouded skies could also be suitable for passage to a lesser extent. Prospects for achieving both of these requirements can easily be checked out on appropriate weather maps, and I have noticed that good matches are common. Large enough areas of clear sky over warm enough seawater can always be found, each having its own effective magnitude, and these areas do in fact seem to be operative as producers of actual early-stage aerial stream beds that enable local vapors to proceed upon their high flying journeys.

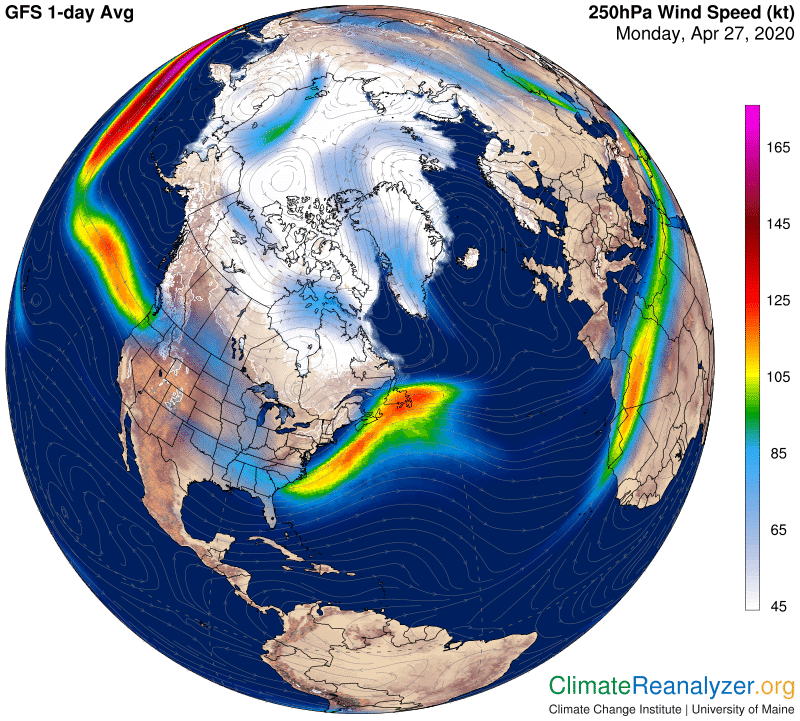

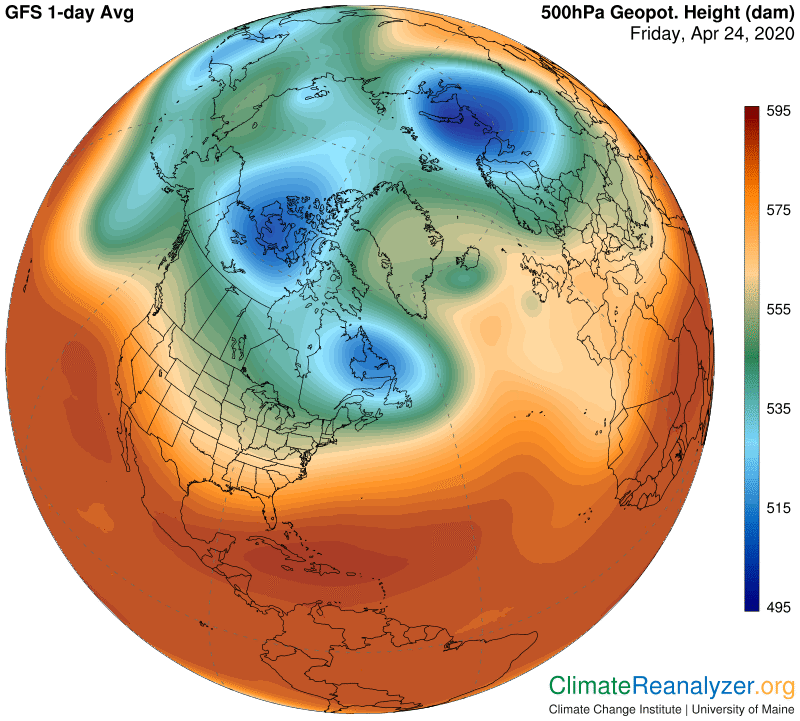

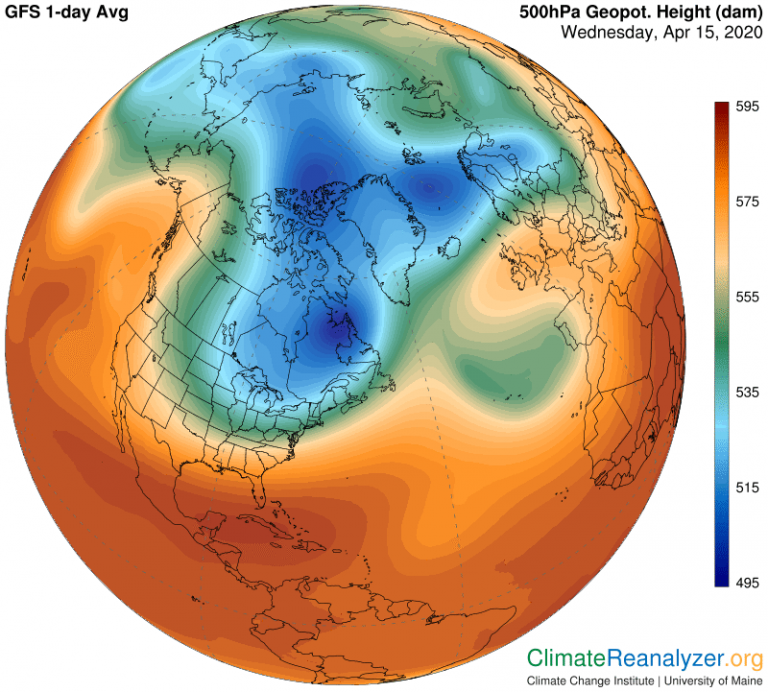

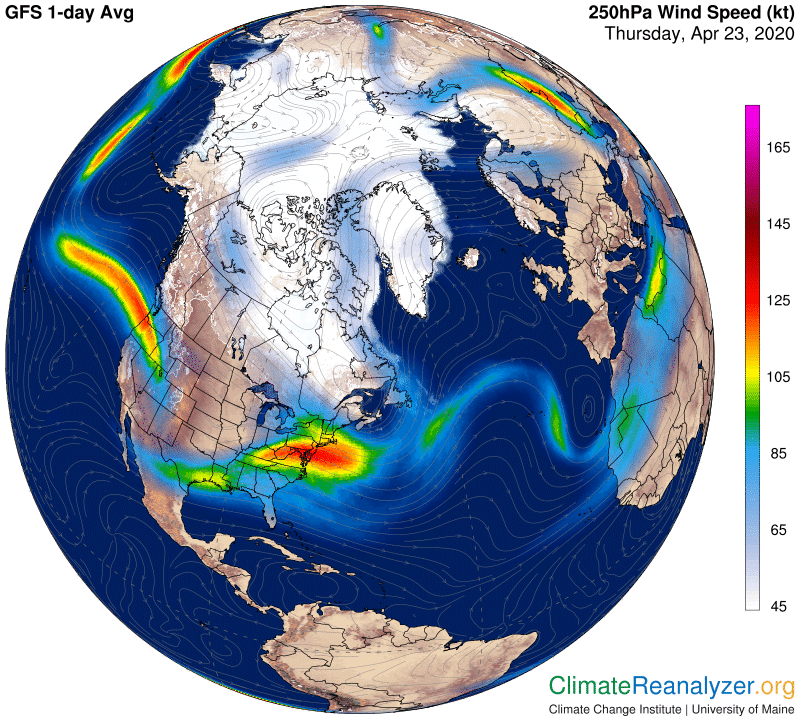

Once a stream bed is in place, and a continuous stream of vapors is rising and leveling off at a high altitude, it should next be picked up and carried away by circulating winds of moderate strength. These winds always run counter-clockwise in the north (clockwise in the south), with a bias toward the pole. Before long they will all run into a fast-moving jetstream-based wind associated with the structural pattern of high-altitude air pressure differences. These jets, and more like them that are later encountered, all have a great influence on the shape of the ongoing pathway of each stream bed, and I believe these same encounters, whenever they occur, have a considerable role in the activation of rainfall. I won’t say any more about it today, but see if you can spot aspects of these various effects along the southeast coast of the US, and beyond, from looking at the following three images:

Carl